Are Creole Languages just "Broken English"? 🌎

All living things have the ability to communicate. This can come in many forms, such as cells using chemical messengers through the process of cell signaling, honey bees “dancing” to explain where and how far away flowers are, or a musician composing abstract lyrics which can have multiple meanings based on the listener’s interpretation. Regardless of the method, communication has been vital to the progression of life on Earth.

Some living things have more advanced ways of communicating, and even the same species can have regional variations. For example, sperm whales use clicking vocalizations known as “codas”, and whales from different parts of the world have been found to have accents. However, research has yet to find a species which has a true “spoken language” on the same scale as humans.

It’s theorized that 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, spoken human language began in order to help with our need for survival. What began as grunts and yelling, has now evolved into something that has allowed you to read this article in one of the most commonly spoken languages in the world, English (or French too if I’ve updated this yet). Today, over 7000 languages are spoken across the world, and linguists say there could be around as many as 31,000 ever in human history. Some have faded from existence, while others have been isolated, or have had their influence spread through means of colonialism, trade, etc. Regardless of their origin, the need to communicate has been a staple to the development of human kind, and a necessity for our survival.

Here we’ll take a closer look at two types of languages: pidgins, and creoles (with a focus on the latter). Both which are directly tied to humans’ ability to adapt and survive, and both which are often not recognized for being languages in their own right. The more we recognize them as such, the closer we might get to prevent them from being lost one day like thousands of others.

Pidgins and creoles are new languages that arise when speakers of different languages come into contact with one another, and have a necessity to communicate. For example, this may happen through trade, or in countries with many different languages, but no common language between different groups. Historically, many have arisen via colonialism, slavery, and indentured servitude.

A pidgin is a type of language that arises suddenly for essential communication. This may occur between groups of two or more. In most cases such as colonialism and slavery, the less dominant group is usually tasked with learning to communicate with the more dominant group. Without any formal education in the languages amongst each other, a simplified grammar and simple vocabulary is adopted. Generally, the vocabulary is heavily based on the dominant, or lexifer language, and the grammar tends to be based on the native languages, however there’s no concrete format as to which language influences which aspect of the pidgin. What is concrete is the fact that it is a mixture of these languages.

When pidgins first develop, they’re generally used in certain functions and are considered “restricted”. This means that they’re used exclusively in certain areas, such as trade or during work. They tend to have a limited lifespan, and end when these relationships have been completed, such as the end of a trade route. However, sometimes pidgins can become “expanded”, meaning they’re used in wider areas such as social and family life. This can occur even after certain relationships end. These expanded pidgins then continue to develop their own grammar and vocabulary, and be influenced from other languages. Structurally, these can be as complex as creoles, however a fine line distinguishes the two.

A creole is formed when a pidgin survives and becomes the native language of the next generation. Possibly the most well known of these languages is Haitian Creole. It’s a French-based creole with influences from African and other European languages, as well as the indigenous Taino language. It has more than 12 million native speakers, making it one of the most widely spoken creoles worldwide, and is recognized as an official language of Haiti. The language began when French colonists and African slaves needed a way to communicate on the sugar plantation fields. Theorized to be either a result of the slave captors purposely using a simplified version of the language thinking the slaves were inferior and incapable of learning, or the slaves attempting to survive given their situation, or a combination, the need to communicate was necessary and forced upon these people.

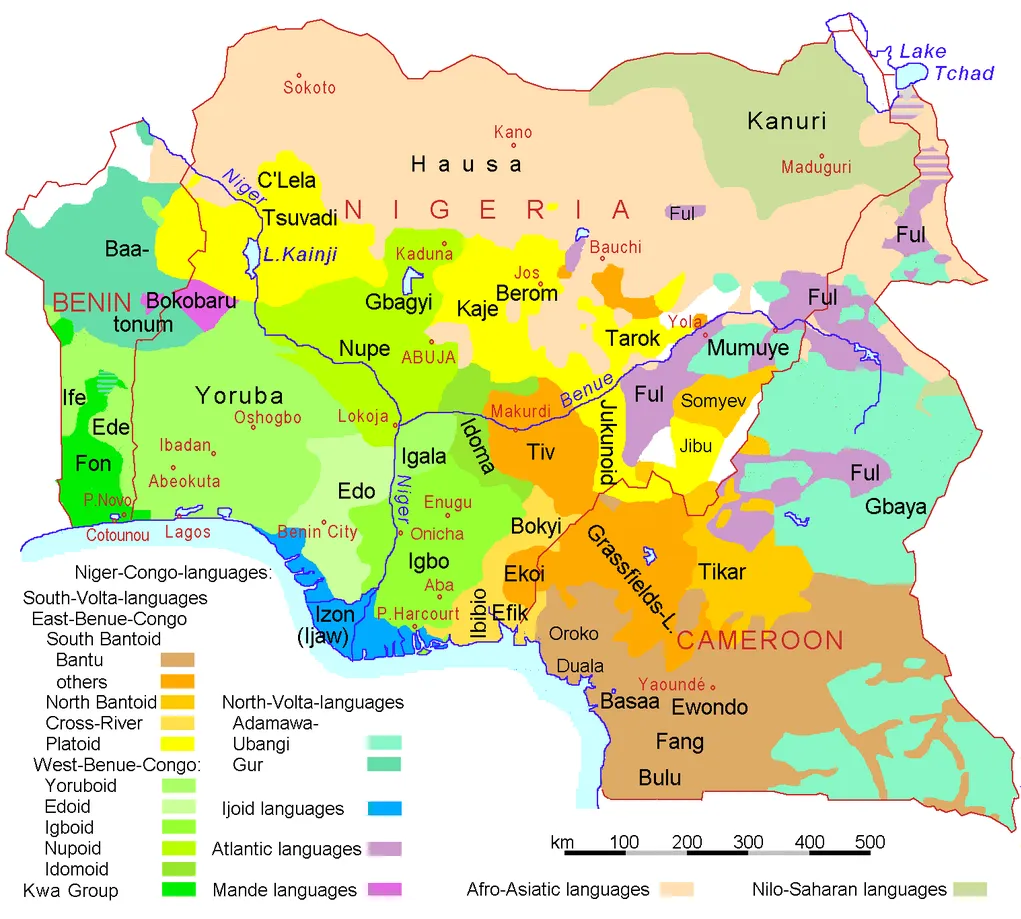

Another example is Nigerian Pidgin. One of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world with over 500 spoken languages, Nigeria’s large population and vast ethnic groups needed a way to communicate effectively with each other. The language initially began as a Portuguese-based pidgin, as the Portuguese were the first from Europe to begin trade. However, over time after different groups came and left, the language evolved to be English-based once the English maintained their dominance of the region, and it continued to evolve after they left as a necessity among the various peoples.

Hundreds of years later, there’s still influences of the Portuguese language on Nigerian Pidgin too. For example, it’s theorized that the word for child, “pikin”, comes from the Portuguese word “pequenino”. When West Africans were then taken as slaves to the West Indies to places like Jamaica, this word evolved to “pickney”. For this reason, many similarities are found between a lot of West African languages like Nigerian Pidgin, and West Indian pidgins and creoles. This can extend beyond words as well, such as sounds and body language. An example of this is “kissing one’s teeth”. This is a result of sucking in air and sometimes pushing your lips out, giving the impression of kissing. It’s used as a sign of disapproval, annoyance, or disgust, and is common within both regions. This gesture has now made its way to places like Canada, the US, and the UK, where a large population of their diasporas reside. Overall, pidgins and creoles pull from a variety of languages in different areas as they evolve and adapt.

Usually with pidgins and creoles, their grammar is condensed in a way that eliminates certain irregularities, and simplifies the conjugation of verbs (if any). Therefore, the nature of these languages often gives the impression that their simplicity means they’re of a lower standard. Although these languages have their complexities, this can result in them not being recognized officially in their native countries, and carry many misconceptions which try to delegitimize them as languages. This is often done even among native speakers. For example, many might reduce them to a slang, an accent, or “broken”, when this is incorrect. However, you can’t really blame people for thinking these things, because most people aren’t familiar with what defines these as languages. If we want to avoid discrediting pidgins and creoles as languages, we need to learn how to define one.

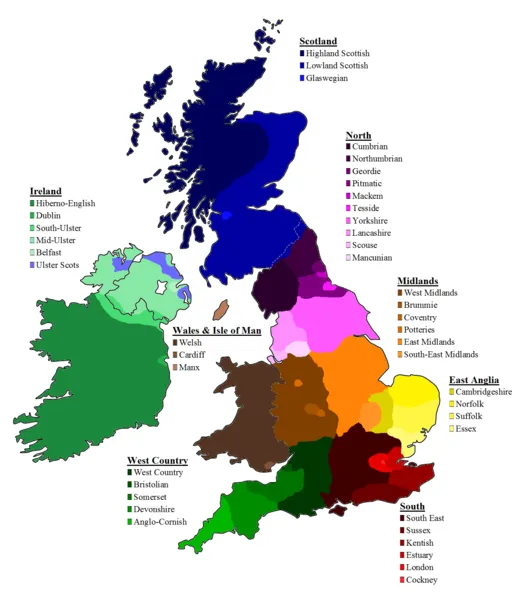

Within every language there is some degree of difference. These variations in a language can result in different regions, and groups of people having different dialects. One way that we define a dialect is that it is a variety of a language that has mutual intelligibility. This means that speakers of these different varieties can understand one another completely (or mostly). For example, you have American English, and British English which are both the same language, but dialects of English. Although they may differ in vocabulary (for certain words), pronunciation (phonetics and phonology), and even grammar, they still remain the same language. Another criteria is that they use the same written standard. For example, let’s say an American and Scottish person have difficulties understanding one another through speech, since the standard language is the same when in written form, you would consider them each dialects of English. Sometimes the term “dialect” and “accent" are used interchangeably, but there are differences.

An accent can be defined simply as pronunciation. For example, people from New York and Texas both speak American English, but one might have a New York accent, while the other has a Southern accent, even possibly a more distinct one based on which region of the state they come from. An accent can also be defined as the application of phonological rules, intonation, and sounds of one language onto another. For example, a native English speaker learning Spanish might pronounce the word “arroz” (rice) without rolling the r, and instead say something like “arose”.

Depending on how you define these terms, a creole could be considered a dialect rather than a language, as it is a variety of the language it’s based on, and the definitions of language and dialect often overlap. However, when most people refer to it as one, it’s done so while generally carrying a derogatory, or disrespectful undertone, like when it’s referred to as “broken”. Additionally, there’s some uniqueness to creoles which separates them from being just a dialect or accent.

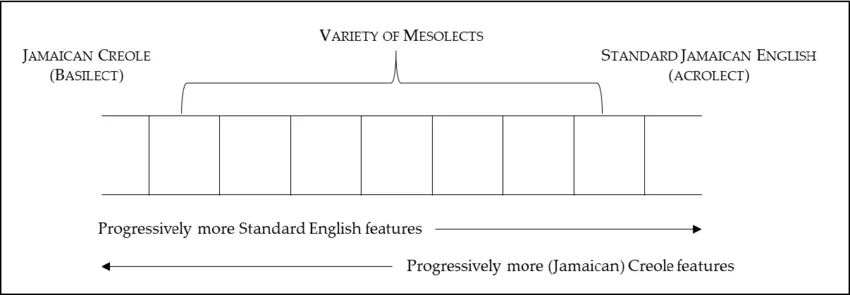

The misconception of creoles being simply a dialect or accent but not a language in its own right stems from the fact that many creoles exist on a spectrum (creole continuum) of varieties of the language, ranging from the most and least similar to the standard language it’s based on. For example, a native English speaker would have a difficult time understanding what someone speaking Jamaican Creole was saying if they were speaking close to the end of the spectrum (basilect), but easily understand someone speaking Standard Jamaican English (a dialect) towards the opposite end of the spectrum (acrolect), just with pronunciation differences, or a Jamaican accent. In everyday conversations, you might have natives speaking somewhere in the middle (mesolect).

The fact that a spectrum like this exists also aids in further distancing the creole from being recognized as a language in its own right. The acrolect is what people might consider to be of higher prestige since it’s what’s generally used in the workplace, politics, media, etc., while the basilect is seen as low prestige since it’s mainly used in informal settings. What natives might do is move their speech closer toward the end which is most closely related to the standard language (acrolect) when speaking. This might be due to the setting, speaking with foreigners, not knowing if the person would understand you speaking closer to the basilect, or unfortunately, being embarrassed as you might be viewed as uneducated if you spoke “improperly”. Linguists tend to refer to the opposite end as the nonstandard language (vernacular), and could be considered as the most natural form of the creole. This term however does not imply that it’s substandard.

Another factor which plays into this narrative is the fact that most creoles have not yet adopted a standardized writing system. As mentioned previously, a dialect can be defined as sharing a common written standard. With many creoles, when people want to type or write something it’ll either be in the standard base language, or with a phonetic representation of the words. This could result in issues even with natives, because some people might interpret the sound of a word differently, and therefore spell it as such. Some do however have a written standard such as Haitian Creole.

Even the name of the language in itself can have negative connotations associated with it, which further adds to this narrative. For example, Chabacano, a Spanish-based creole language in The Philippines, comes from the Spanish adjective meaning “vulgar”, or “tacky”. This is also seen in Jamaican Creole, known by natives as Patois/Patwa, where “patois” comes from the Old French term meaning “clumsy”, or “uncultivated speech”. In order to see what sets creoles apart, let’s visually compare some to their predecessors.

Here is an example of a Jamaican Creole translation from Standard English. This shows that the word order is similar to that of Standard English:

Standard English

I don’t know what they are saying.

Jamaican Creole

Mi nuh nuo wah dem ah seh.

Word for Word

Me no no what them are say.

Here is an example that shows that verbs aren’t always conjugated the same way that they are in Standard English to indicate tense, and rather opt for time markers instead. Also, that not all vocabulary is shared with the base language:

Standard English

They ate dinner.

They are eating dinner.

They are going to eat dinner.

Jamaican Creole

Dem did nyam dinna.

Dem ah nyam dinna.

Dem guh (fi) nyam dinna.

Word for Word

Them did eat dinner.

Them are eat dinner.

Them go (for) eat dinner.

Similarly, Haitian Creole also lacks verb conjugations and opts for time markers to indicate tense. Compared to Standard French, it also uses “ap” as a marker for the present progressive tense, which Standard French lacks (uses a phrase instead – “etre en train de”):

Standard English

I went to the store.

I’m going to the store (in the process of going, right now).

Standard French

Je suis allé(e) au magasin.

Je suis en train d’aller au magasin.

Haitian Creole

Mwen te ale nan magazen an.

Mwen ap ale nan magazen an.

Word for Word

Me went to store the.

Me go to store the.

There are also some features of Jamaican Creole which are not present in Standard English, such as a distinct second person plural pronoun, “unno”. This comes from the Igbo pronoun “únù”, and is also seen as variations throughout the West Indies in languages such as Guyanese Creole (“ayuh”, “ayuhdeez”), and Trinidadian Creole (“allyuh”).

Standard English

Where are you guys (plural)?

Jamaican Creole

Weh unno deh?

Guyanese Creole

Weh ayuh deh?

Word for Word

Where you (plural) there?

Due to the compact nature of these languages, words are also often shortened, or repurposed and given a different meaning. For example, “nuff” deriving from “enough”, instead means “a lot” in Jamaican and Guyanese Creole. Additionally, “people” are sometimes just referred to as a singular “body” in Guyanese Creole.

Standard English

Not a lot of people were there.

Guyanese Creole

Nah nuff body bin deh.

Word for Word

No enough body been there.

Unique words in the standard language it's based on also might have more simpler, literal meanings. Also, asking questions are often done through rising intonation, along with inverting pronouns and verbs:

Standard English

Why is he flaring his nostrils like that? Can’t he breathe properly?

Jamaican Creole

Wha mek him skin out him nosehole suh? Him cyaan breed prappa?

Guyanese Creole

Wha mek e skin out e nosehole suh? E cyan breed prappa?

Word for Word

What make him skin out his nostrils so? He can breathe proper?

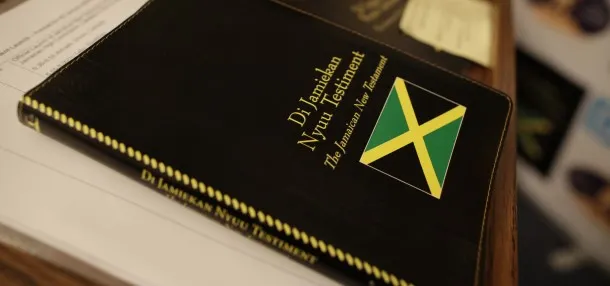

As you can see, these languages are not “broken”, but rather condensed and repackaged in a way that gives it a uniqueness compared to its base predecessor. If we continue to discredit them, they might be lost to history like thousands of other languages. It’s not like this everywhere though, and many places are seeing a shift in their approach. For example, Haitian Creole although mainly used informally, is also used in formal, and public places such as schools, political meetings, and public functions. Also, literature such as the Holy Bible has been translated into a Jamaican Creole version. Although there’s no standard writing system, this is a step forward in the right direction.

To conclude, language travels like people, changing, learning from others, and evolving. Pidgins and creoles are a representation of human history, and an embodiment of mankind’s ability to adapt and survive based on their environment. Whether these people were considered a servant, or slave, the fact remains that they were exploited and given harsh punishment, poor working conditions, and treated like less under the imbalance of power that continues to plague human kind. The idea of being better than another human resulted in atrocious acts, yet those on the receiving end were able to endure, and made something forced upon them into their own.

If you and your family come from a place where these are spoken, I challenge you to change the narrative. Try to take a deeper look into your culture, and how you communicate with your family, friends, and people of your background. Stop discrediting the legitimacy of your native language, and be proud of it. Stop referring to it as “broken” when it’s simply been molded into something new, and educate others whenever they incorrectly refer to it as that. You owe it to those before you who endured atrocities and hardships, but still kept moving forward. It’s a part of your history, and culture, and makes you who you are.